OHIO CONNECTION: Resident

Cleveland

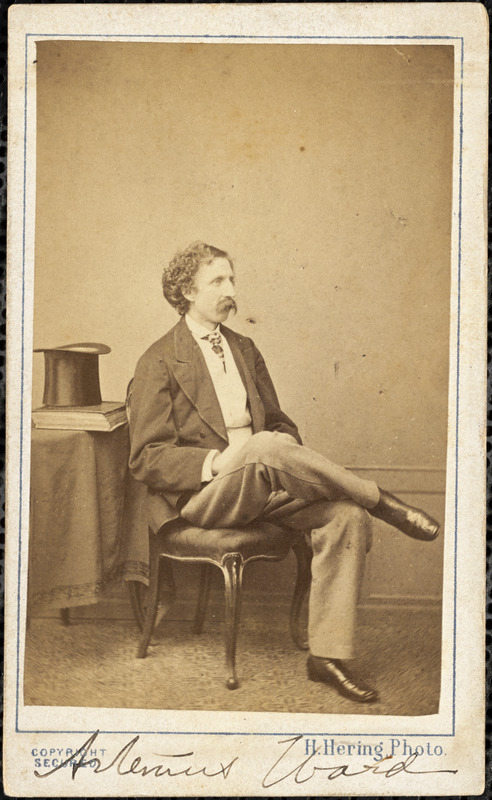

Born on April 26, 1834, humorist Charles Farrar Browne (aka “Artemus Ward”) grew up in Waterford Flat, Oxford County, Maine. His mother, Caroline Eliza Farrar Brown, was a freethinker descended from the first Puritan settlers of North America in Plymouth, Massachusetts. His father, Levi, was a liberal-minded Congregationalist whose grandfather, Jabez Brown, had been a lieutenant in the French and Indian war and an adjutant in the Revolution. Outside of his job as a civil engineer, Levi was also a Justice of the Peace, selectman, and a member of the state legislature. Browne’s sense of humor was “hereditary on the paternal side, his father especially being noted for his quaint sayings and harmless eccentricities.” (C.D. Warner, et al., 1917) Levi died when he was 49 years old, abruptly ended Browne’s formal schooling as it was expedient for the thirteen-year-old to obtain gainful employment.

Having moved, alone, to Lancaster, Coos County, New Hampshire, the “abnormally tall,” “gawky” and gaunt Browne found work as a typesetter to James Madison Rix, a lawyer/politician who published the Weekly Democrat. Residing in the Rix household, Browne occupied a ramshackle room “with a rickety bedstead … a torn straw mattress, a table, and a three-legged cook-stove …” Rix had him write articles, set type, and collect the cash (or its equivalent in produce) owed to the paper by its subscribers. Eliza, Rix’s teenage daughter, would often ride out with Browne as was he inclined to swap jokes and stories. When, after nearly a year had passed, Rix was so scandalized by Browne’s apparent lack of application and verve, he dismissed him, with a dollar in his pocket and the exhortation that he get some schooling.

When his elder brother, Cyrus, took over the Norway Advertiser, Browne made his way to Norway, Maine, to join him. Although not a regular student of the Norway Liberal Institute, Browne, in his spare time, was nonetheless a thespian in its Dramatic Club; a frequent contributor to its student newspaper, the Carpathian Rill; and a lauded member of its Debating Society. On every occasion that he was due to speak, standing room only would be the norm for the hall. Almost every citizen of Norway was aware of when he was scheduled to speak. When Cyrus’ endeavors proved to be a bust, he sold the paper to the Institute’s principal, Mark H. Dunnell, who changed its name to Pine State News. Dunnell was ultimately driven past endurance by the jests and japes of his teenage employees (e.g., one lad had a metal pipe made by the town tinsmith so that the boys could push it through a clandestinely bored floorboard hole to suck up rum from the casks stacked up to the ceiling in the storeroom below). Flabbergasted at just how much money a newspaper ate up, Dunnell fired everyone and turned the business over to his creditors.

Upon the Advertiser’s and Pine State News’ demise, Browne moved to Augusta, Maine, but stayed only a few weeks before relocating to Skowhegan to work as a compositor for Moses Littlefield on his newspaper, the Weekly Clarion. This fifteen-year-old teen’s peripatetic existence did not end quite yet as he inexplicably vanished one night by climbing down a bed-cord from his bedroom window and began, in the dead of night, the trek down the Kennebec to Gardiner, where he raised enough change to reach Waterford.

Backed by letters of recommendation, Browne traveled to Boston and presented himself to Messrs. Snow and Wilder, proprietors of the weekly humor journal Carpet Bag. Browne was engaged as a journeyman typesetter and journalist. With élan, Browne befriended Boston’s theatrical community, noting their individual personalities, mannerisms, quirks, and ticks. With considerable aplomb, he burlesqued these cultural giants in articles and as a raconteur.

Having spent three fruitful years in Boston, Browne was driven not only to seek a new job but to travel westward.

Browne’s first experiences in Ohio occurred in Cincinnati where he found employment as a substitute printer. Having seen an advertisement for a teacher’s job in Kentucky, Browne applied for it and was hired. Frail, he discovered himself no match for his brawny pupils. Conceding that maintaining discipline would be a fool’s errand, he returned to Cincinnati without waiting to be paid.

Discovering that jobs were available in Tiffin, Ohio, he made his way there and remained for almost a year before venturing off to Toledo, joining the Commercial.

Quickly, he went from being a compositor to an editor. His fame spread like wildfire — so much so that Joseph W. Gray, founder, and publisher of the Cleveland Plain Dealer, offered him the job of city editor at $10 a week upon the retirement of the previous editor, James D. Cleveland. Browne’s first day of work at the Cleveland newspaper was October 25, 1857.

An afternoon newspaper, The Plain Dealer was democratic in policy. It was situated in an “unkempt and unwholesome building at the corner of Vineyard and Superior streets, dingy, dirty, and uncomfortable. The editorial-room was a shabby loft, furnished with rickety pine tables and half dismembered chairs. In short, it was a ‘hole’ such as the old-style printing-office was wont to be . The new man (Browne) worked with the crowd at a table in the corner that joggled as he wrote, amid the scratchings of other pens and the constant howls for ‘copy’ from the composing-room aloft.”

On January 3, 1858, three months after his joining the Plain Dealer, Browne published the first of his “Artemis Ward” letters. “Artemus Ward” was a fictitious, illiterate impresario of a traveling side-show that consisted of an elephant, a bear, a kangaroo (which, along with his hyena, escaped and ran amok in Toledo), six snakes (including a boa constrictor), a skulk of tame foxes, and a wax works. Ward wrote in dialect with proper spelling, grammar, and punctuation thrown to the wind. It was pure social satire. He often spiced his missives with humous barbs that held people, places, and habits up to ridicule. Browne would continue to feature letters from “Artemis Ward” over a two-year period. Justly proud of his achievement, he submitted copies to Vanity Fair magazine, hoping to make his celebrity more widespread. Believing that the exclusivity that Gray wanted for his talent warranted additional remuneration, Browne argued his worth and that it should come at a higher price than what Gray was offering. Gray terminated Browne’s employment with the Cleveland Plain Dealer on November 10, 1860.

When Vanity Fair offered him a job, Browne left Ohio and relocated to New York City.

Browne gambled that he could succeed against the odds, taking his humor on the lecture tour circuit. Whereas other lecturers sought to moralize and civilize people, Browne was intent on showing them a great time. Armed with a massive arsenal of jokes, witticisms, and Artemis Ward letters, Browne had people rolling in the aisles across the country and overseas.

Tragically, while touring England, he contracted tuberculosis and died in Southampton, on January 23, 1867, at the age of 33. His remains were brought back to the United States and were laid to rest in Elm Vale Cemetery in the town of his birth, South Waterford, Oxford County, Maine.

Mark Twain himself, the quintessential American humorist, held Charles F. Browne in high regard, calling him “one of the great humorists of our age” in an address in Albany, New York, on November 29, 1871. Twain and Browne became friends and performed on the same stage on a number of occasions throughout Browne’s lecture circuit career.

Sources and Additional Resources

Seitz, Donald Carlos. 1919. Artemus Ward (Charles Farrar Browne): A Biography and Bibliography. New York: Harper & Brothers.

The Complete Works of Artemus Ward by Artemus War (aka Charles Farrar Browne) via Project Gutenberg

“Cleveland’s Artemus Ward remembered as pioneer of stand-up comedy” (ideastream public media, Feb. 4, 2022)

Charles Farrar Browne: Past Masters Project (Cleveland Arts Prize)

Artemus Ward’s individual books:

- Artemus Ward His Book (1862)

- Artemus Ward His Travels (1865)

- Artemus Ward Among the Mormons (1865)

- Artemus Ward in London (1867)

- Artemus Ward’s Panorama (1869)

- Artemus Ward’s Lecture (1869)