Illicit love letters written in secret code. The impact “secretaries” had on a famous author’s work. The myth and allure of the West. Contrasting portrayals of rugged masculinity and romance. An enemies-to-lovers story featuring a bold, headstrong young woman and a pouting, enraged young man. Hear more about these topics and others by listening to “The Secret Life of Zane Grey,” a Page Count podcast episode focusing on the Ohio-born author who popularized the Western genre in the 1920s and 1930s.

This conversation, which features Lucas Fralick from the Wyoming Center for the Book; Don Boozer, Coordinator of the Ohio Center for the Book; and Ohio Center for the Book Fellow and Page Count host Laura Maylene Walter, initially focused on Grey’s novel Wyoming but ultimately covered so much more. During her research for the episode, Laura uncovered many additional tidbits about Grey that she didn’t have time to share on the pod. So here we are!

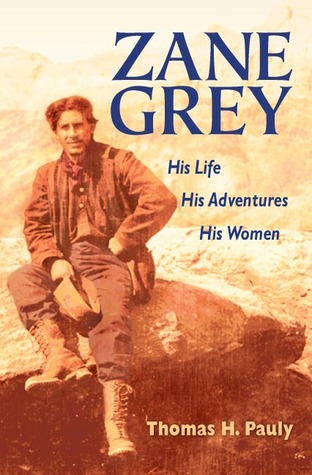

First, Laura credits the compelling, exhaustive 2005 biography Zane Grey: His Life, His Adventures, His Women by Thomas H. Pauly as her main source for podcast research. Pauly’s biography provides detailed, illuminating context surrounding the life and work of Zane Grey, from his years working as an unlicensed dentist to his professional baseball days, his writing triumphs and failures, his many affairs, and the help he received from assistants and secretaries.

Here are just a few fast facts about Grey’s life gleaned from this biography:

- As a kid growing up in Zanesville, Ohio, Zane Grey was no stranger to schoolyard fights. He hit classmates with rocks and bricks, and he apparently clubbed his neighbor’s chickens to death.

- He followed in his father’s footsteps by practicing dentistry as a young man. At the time, cocaine was used as an anesthetic in dentistry practices, and when Grey ignored his father’s warnings not to administer cocaine to “frail patients” and an elderly man nearly died in his care, he “hastily left town.”

- Zane Grey was a poor student, a source of insecurity for him, and he did not finish high school.

- At age sixteen, he was arrested in a brothel.

- While Grey practiced dentistry without certification for a time, he eventually entered dental school at the University of Pennsylvania (which admitted him based on experience but also his “athletic prowess” as a baseball player).

- Grey played baseball for Penn and also for the Capitols in Columbus, Ohio.

- In 1894, at the age of 22, he was arrested after a baseball game in a paternity suit. His father paid $133.40 “to cover the full cost of the case.”

- Grey was a competitive fisherman and set various world records for catching tuna, tiger sharks, and great white sharks throughout his life. At times, drama with his fellow fishermen caused him anguish and ultimately resulted in him resigning from the Tuna Club.

- When he fell on hard financial times, Grey endorsed Camel cigarettes even though he despised smoking.

- In October 1939, after holding a book signing in Los Angeles for his novel Western Union, Grey suffered a heart attack and died. His wife Dolly was by his side.

Writing Highs and Lows

Laura could have hosted an entire second podcast surrounding the up and downs of Grey’s writing career, his very relatable struggles with publishing and how his books were positioned, and the criticism levied against his work. For now, here are some glimpses into his writing struggles and triumphs, courtesy once more of Pauly’s biography:

- When Grey’s first novel, Betty Zane (1903) was rejected by publishers, he paid $500 to publish it with Charles Francis Press.

- In 1911, following a discussion with a publisher, Grey bemoaned the industry and his own work, expressing that he was “unable to see what use there was in me writing.”

- When his editor asked him to analyze a bestseller for research, Grey proclaimed that the book was filled with “poor wooden writing” and that he “would be ashamed to have my name on such a book.”

- Later, he wrote of this editor: “He would sacrifice genius for the ‘best-seller.’ It is simply that appalling thing commercialism. I have been bitterly hurt . . . My work is not to be what this critic advises, or that publisher wants. It is to be what I cannot help but make it. I am driven. I’ve got to write what I feel and see and think. But I am not yet an artist.”

- By 1920, Grey was a well-paid and in-demand writer, but nonetheless, he struggled with how publishers positioned his work. His publisher argued that advertisements for his novels, for example, did not “fit” the New York Times readership.

- Grey often said women inspired his writing, but he was also a harsh critic of women, especially concerning modern ways of dressing, dancing, and so on. In The Call of the Canyon, a woman’s assault is essentially blamed on her attire.

- As his writing grew more popular, Grey increased his output to make money and keep up with demand. He was reported to have once written six chapters in six days, and at least once wrote 10,000 words in a day.

- He was criticized for formulaic writing, but such criticism didn’t harm his popularity with readers.

- Upon completing Wilderness Trek, Grey wrote: “I have just finished the largest, and perhaps the profoundest of all my novels.” Ten days later, after rereading it, he changed his tune: “At first I thought it wasn’t bad. But I think now it was.” (Every writer can relate to this 100%.)

Berenice Campbell

In the podcast episode, Laura shares how the hitchhiking sections of Wyoming were “inspired” by the real-life adventures of Grey’s assistant, Berenice Campbell. Here is what Thomas H. Pauly wrote in his biography of Grey:

At the time that she initially informed him about her hitchhiking adventures, Berenice revealed that she hoped to convert them into a novel, and Zane encouraged her with helpful suggestions about structuring and developing the story. When he later realized that her work was less promising than Mildred’s, he took it over, reworked it, and sold it for serialization as “The Young Runaway” to the Pictorial Review for $30,000. Grey rewarded Berenice with a contract granting her 15 percent of the royalties from the novel . . . Berenice took her agreement to an attorney shortly after her relocation to San Francisco, and Dolly had to negotiate a settlement. She handled the matter so tactfully and so amicably that Berenice lowered her royalty to 5 percent in return for a typewriter and an automobile that Dolly deducted as a business expense.

In an earlier biography of Grey, Maverick Heart: The Further Adventures of Zane Grey by Stephen J. May, the terms were slightly different: only 10 percent originally, compared to 15 percent:

“In the early 1930s, unknown to Dolly, Zane entered into a contract with a young woman named Berenice Campbell. The resulting flap cost Zane dearly. In 1929 Berenice Campbell, age twenty-one, hitchhiked alone from Missouri to Wyoming, keeping a journal of her experiences on the road. She later sent the journal to Zane Grey, who was so impressed by her independence and spirit that he offered her a royalty of 10 percent on the earnings from a book he would write about her trip. For a brief time Campbell served as Grey’s secretary, but she soon left his employment . . . When she was not paid her share, Campbell sued Zane.”

In her additional research into this matter, Laura reached out to the Zane Grey’s West Society and received several helpful responses from members and Zane Grey enthusiasts. Of particular assistance was Dr. Kevin Blake, who offered the following information via email:

“Grey wrote the book in early 1932. As you know, the opening of Wyoming (which was serialized as the The Young Runaway in 1932 and published in book form in 1953) was based on Berenice Campbell’s hitchhiking adventures in 1929. Campbell made a claim to 10% of the royalties based on a contract Zane Grey wrote when they first met. At the start of the Great Depression, the Greys were in poor financial shape at this time, both in terms of income and tax debts that the IRS claimed were owed.

“Throughout the summer of 1932 Lina (Dolly) Grey negotiated a settlement with Berenice Campbell for $1,500 that kept the story out of the press. This episode convinced Dolly that they must incorporate or at least enter into a partnership agreement (Missouri Review 1995, 159-162; Pauly 2005, 294; Kant 2008, 313-319). Indeed, in November of 1932 Zane Grey, Inc. was formed to help protect the Grey family financially, and to keep Zane Grey from having the sole authority to enter into contracts like the one he had signed with Berenice Campbell.”

Laura thanks Dr. Blake not only for this information, but for sharing the scanned cover images of Wyoming and the Pictorial Review that can be seen in this blog post and in some of Page Count’s promotional materials. In addition, Dr. Blake graciously shared his article “Zane Grey and the Historic Trails of the Great Plains,” which Grey aficionados may read here in full by clicking here.

Riding Into the Sunset

Is there even more to share about Zane Grey, Wyoming, and the myth of the West? Yes! But alas, it’s time for us to untack this particular horse and put it out to pasture. Laura highly recommends Zane Grey: His Life, His Adventures, His Women by Thomas H. Pauly as well as the resources available via Zane Grey’s West Society.